UnicodeFix: The Day Invisible Characters Broke Everything

From Frustration to Fix

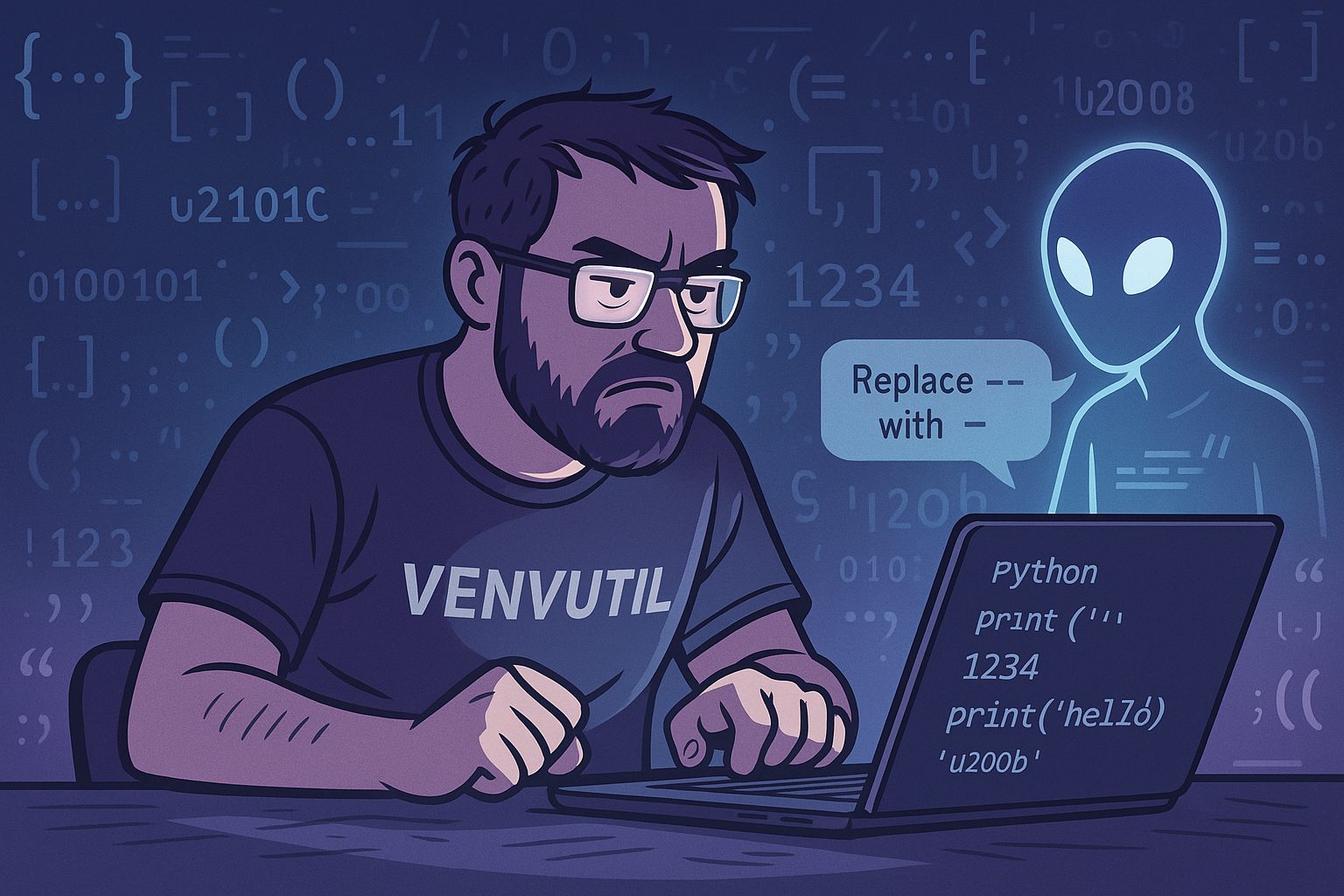

This all started maybe five days ago with a Python script that just wouldn’t run.

Not because of logic errors. Not bad syntax.

No, this was something worse — something invisible.

I had copied some code straight out of Cursor’s chat panel into a file. Looked fine. Ran it.

Boom: IndentationError: unexpected indent.

I stared at it for a while, pulled my hair a bit. I knew the indentation was fine.

It was flat code — no nesting, no tabs. I even did a global find-and-replace on the leading spaces.

Same result.

The idea that it could be Unicode? Didn’t even occur to me.

Eventually, Cursor’s own assistant piped up and said:

“Oh, you’ve got hidden Unicode spaces at the beginning of each line. Strip those out and it’ll run.”

And sure enough — it did.

That one invisible character wasted hours.

It looked like whitespace. It acted like whitespace. But it broke the interpreter.

And that’s when I started looking around.

Turns out, I wasn’t the only one.

I hit Reddit and started seeing post after post:

“Cursor broke my code with invisible stuff.”

“VS Code is inserting Unicode garbage and my linter can’t catch it.”

“Why does AI code have these weird characters no human would ever type?”

One comment hit a nerve:

“AI code has a Unicode accent now. Professors can tell.”

And that’s when it clicked. This isn’t just annoying. It’s serious.

These invisible Unicode characters — zero-width spaces, left and right smart quotes, BOMs, and friends — can break everything from Python scripts to YAML configs to HTML layouts.

In some cases, they even flag work as AI-generated.

Imagine working hard on something, refining it, shaping it — only for it to be dismissed because the quotes aren’t “ASCII enough.”

It brought back flashbacks from Japan, too — the dreaded mojibake, when UTF-8 and UTF-16 would collide and your characters would turn into incomprehensible glyph soup. Rendering issues. Encoding mismatches. Terminal output that looked like alien language.

These weren’t just technical nuisances. They were trust-breakers.

I realized: we needed a fix. A proper tool. Something immediate, local, and clean — to give people back control over their text.

Dictation = Velocity

One thing made this project move faster than anything else: I wasn’t typing.

I’d just wrapped up my Willow Voice trial on macOS and was on the fence. I figured I’d give it one more go.

And it was like flipping a switch.

Suddenly, instead of chasing ideas with my keyboard, I could speak them aloud as fast as they came to me.

Function names. Log messages. TODOs. Architecture decisions. Even this blog post — much of it dictated, not typed.

Willow handled the flow like a pro: no filler, no “uhhh”, no lag between thought and code.

In a way, it made collaboration with my AI assistant more fluid too — like having a real-time partner in a shared headspace. I wasn’t juggling syntax; I was thinking about what I wanted to build. The layers, the UX flow, the traps to avoid — and the fixes.

Honestly? That single shift cut development time by at least 30%. Maybe more.

Getting It to Click

Once the core functionality was solid — stripping quotes, normalizing dashes, vaporizing zero-width ghosts — the question was: how do we make this easy for anyone to use?

I didn’t want this to live only in the CLI. Sure, it could work in pipelines, inside Vim via %!, or piped from pbpaste. But not everyone lives in a terminal.

That’s when I turned to macOS Shortcuts — and that’s where things got weird.

Shortcuts seemed simple at first. Just a shell command, right?

But it quickly became clear: to pass file arguments into a proper Python environment with a conda-managed virtualenv, I needed a full login shell, .bashrc execution, and some clever quoting tricks.

One misstep and the shortcut would fail silently, or worse — run without activating the environment.

Even getting arguments passed in cleanly required tweaking the bash -l -c incantation to include both the Python script and the parameters outside the quoted string. Subtle stuff, but critical.

And yet, when it finally worked — right-clicking one or more files in Finder, selecting “Strip Unicode”, and instantly generating .clean.txt outputs — it felt like we’d stitched together something native. Something that belonged there all along.

It was clean, it was fast, and it worked exactly as you’d expect.

Mission complete? Not quite — but the bones were solid.

The Problem Was Bigger Than Expected

At first, it seemed simple enough: strip out invisible Unicode junk and normalize spacing.

But like most rabbit holes in computing, the deeper we looked, the more twisted it got.

It wasn’t just zero-width spaces or sneaky joiners that were breaking things.

It was smart quotes, em-dashes, weird hyphens, and other typographically “fancy” Unicode that had no business being inside a code block. Stuff that wouldn’t break your editor, but would break your parser.

Quotes that looked like this — “ ” — instead of this — “ “.

Characters that rendered fine on macOS or a web page, but blew up inside Python, YAML, or Markdown.

And the real kicker? They were almost impossible to spot unless you were really looking — or digging with a hex editor.

I realized it wasn’t just an inconvenience. It could affect everything:

- Code execution

- Web rendering

- AI detection

- Text indexing

- Compatibility between systems

You name it.

Redditors were screaming about it.

I was quietly screaming too — holding open a hex editor and shaking my head.

The more we dug, the deeper it got.

I had my assistant generate a whole suite of test files: filled to the brim with Unicode landmines.

Some were invisible. Some were misleading. All of them were traps — not academic samples, but real-world mimics of AI-generated content copied from ChatGPT windows, web pages, and embedded chat panels.

We weren’t just “cleaning up whitespace” anymore.

We were building a normalization engine — one that could take in all that appearance-driven noise and distill it down into clean, predictable, ASCII-safe content without breaking intent.

- A left or right smart quote? Normalized into

". - An en-dash or em-dash? Flattened into a

-.

No semantic loss. Just clarity, restored.

This wasn’t a one-off patch anymore — it was shaping up to be a reliable bridge between messy, over-encoded text and what a compiler, parser, or linter actually expects.

That’s when we knew: we weren’t just solving our problem.

We were solving a growing, urgent problem for everyone — and doing it fast.

—

Building a Smarter, Tougher Tool

The first phase was to make a basic pipe: read in a file or a stream, scrub out the bad Unicode, normalize smart punctuation, and write a clean file.

At one point, we considered doing it with pure sed, awk, or some bash wizardry. But once you start needing context-aware replacements — like turning a left quote and a right quote into a single plain ASCII quote — those tools hit a wall fast.

Python was the right hammer for this nail.

We kept the script lightweight.

No crazy dependencies. Just the standard argparse, re, a tiny bit of filesystem handling, and the excellent unidecode library to fill in the heavy lifting.

After a few iterations — and a lot of piping weird Unicode test blobs through it — the core script was done. It:

- Normalized all smart quotes and dashes

- Stripped hidden Unicode like zero-width spaces and BOMs

- Worked on any file or STDIN

- Wrote clean

.clean.txtversions of files

Simple. Fast. Solid.

Shortcutting Into the Future

Now, getting the command-line tool working was great —

but how do you make it truly frictionless for users?

Enter macOS Shortcuts.

This was an unexpected turn. I hadn’t seriously touched Shortcuts before — not since the old Automator days.

But digging into it, I realized Shortcuts could:

- Trigger from the Finder right-click menu

- Pass selected files as arguments

- Run shell scripts in the background without opening a terminal window

It sounded perfect… and it almost was.

Shortcuts is powerful, but getting it to correctly invoke a bash login shell, preserve the environment, and pass file arguments properly took some serious trial and error.

We had to:

- Force Shortcuts to launch

bash -l -c - Source the

.bashrcto set up the Conda Python environment - Handle quoting and argument expansion carefully so multiple files could be passed cleanly

There’s no real documentation on this.

You either figure it out or you don’t.

But when it finally worked — being able to select a bunch of files in Finder, right-click, and instantly strip all Unicode quirks without even touching the Terminal — that was magic.

It felt like something that belonged in macOS all along.

Pro-tip

If you’re using a VS Code type editor like Cursor, Windsurf, or any others with the Vim extension installed, macVim, vim, vi, or any other editors which can use external programs as a filter, you can simply paste your text into the editor and then do the following:

:%!cleanup-text

This will filter all the Unicode/UTF-8 and replace it with the closest ASCII characters.

Get It

If you found all this helpful, you may download the GitHub repository from the link below. If you find the tools useful, it would be great if you could help support our work at:

Get it on my GitHub: https://github.com/unixwzrd/UnicodeFix

Let us know what features you might like to see in the future.