Parental Alienation Awareness - Part 4

4. Divorce, Custody Disputes, and the Legal System

Parental alienation often comes to the forefront in the context of divorce and custody battles. Here, we examine how common high-conflict divorces are, how often alienation features in these disputes, and how courts have been handling such cases - including errors and reforms.

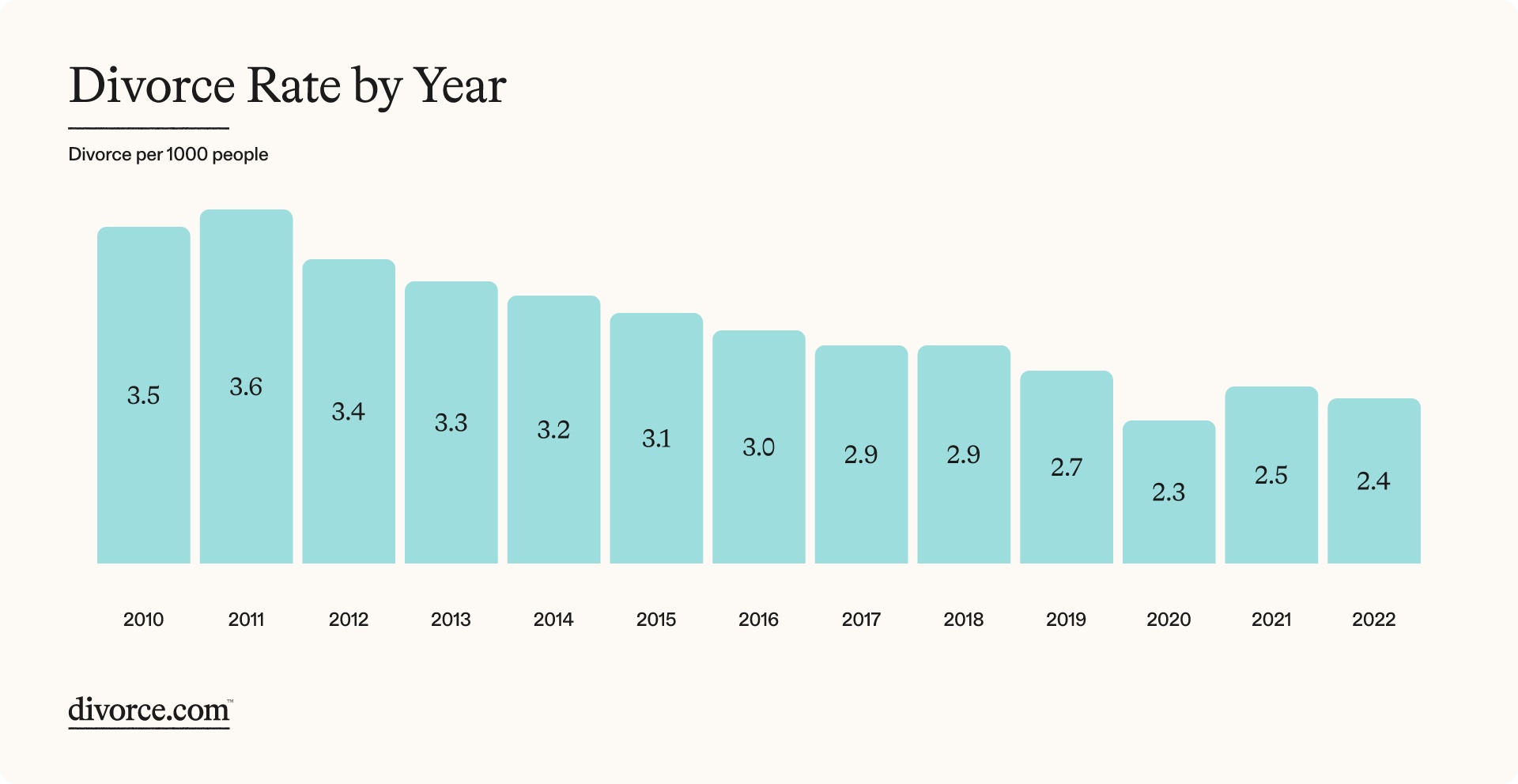

Divorce rates and custody context: In the United States, divorce has been relatively common, though it’s declining in recent years. As of 2020, there were approximately 630,000 divorces nationwide (covering 45 states and D.C.), and by 2022 the annual number of divorces was around 674,000 (2.4 divorces per 1,000 population)[12]. This represents a significant decline from a decade earlier - the divorce rate was about 3.6 per 1,000 in 2010 versus 2.4 in 2022 (see Figure 1). Fewer marriages are ending in divorce now than in the 1980s-2000s. However, the majority of divorces that do occur involve children. Estimates vary, but roughly 50-65% of divorces include at least one child under 18. In other words, every year hundreds of thousands of American children experience their parents’ separation, and a subset of those separations devolve into high-conflict custody disputes.

Figure 1: U.S. Divorce Rate per 1,000 People, 2010-2022. The divorce rate has declined over the past decade (from about 3.6 in 2010 to 2.3-2.5 in recent years). However, a persistent minority of divorces remain high-conflict, often leading to protracted custody battles.

Out of all divorces, research suggests roughly 10-20% are “high-conflict” - meaning the parents engage in intense, ongoing litigation or animosity post-separation[13]. One often-cited statistic is that about 1 in 5 separating couples fall into a high-conflict pattern that can last years. Within this high-conflict group, parental alienation is frequently a core issue. In fact, officials from the UK’s Family Court Advisory service (CAFCASS) stated in 2014 that parental alienation was a factor in ~80% of the most intractable custody cases[7]. They estimated around 200,000 family court cases per year in England/Wales had some evidence of alienating behaviors. Likewise, American psychologists have noted alienation is a common theme among those 10-20% high-conflict divorce cases that require repeated court intervention.

Using earlier U.S. estimates, Dr. William Bernet deduced that since about 20% of children have parents who are divorced/separated, and about 25% of those separations involve high conflict, and about 25% of high-conflict cases result in an alienated child - that yields roughly 5% of divorced families (or ~1% of all kids) where parental alienation occurs in a severe form[5]. While the exact percentages can be debated, it’s clear that each year tens of thousands of custody disputes involve allegations of one parent undermining the other, and courts are increasingly aware of the concept of parental alienation (for better or worse).

Court recognition and missteps: The legal system’s response to parental alienation has been fraught with challenges. Courts struggle to balance allegations of alienation with allegations of abuse, and to discern the child’s true best interests amid conflicting narratives. There have been both successes - cases where courts identified a toxic situation and intervened appropriately - and failures, sometimes catastrophic, where courts “got it wrong.”

One major concern is when courts fail to recognize genuine alienation. Sometimes a manipulative parent continues to violate visitation orders or turn the child against the other parent, but the courts don’t step in decisively (due to lack of proof, court delays, or skepticism about the concept). The result is the alienation progresses until the targeted parent is effectively erased from the child’s life. Advocates highlight many cases where judges were too slow to enforce custody orders or sanction an alienating parent, essentially enabling the psychological abuse to continue. The prevalence of such failures is hard to quantify, but anecdotal evidence suggests it’s common for targeted parents to exhaust their resources in court only to still lose their relationship with the child due to lack of timely intervention.

On the flip side, another grave issue is when courts misidentify alienation - punishing the wrong parent. This typically happens in cases where one parent claims the other is abusing the child, and the accused parent responds by claiming “parental alienation” (i.e., “the child only says I’m abusive because my ex has brainwashed them”). Research by professor Joan Meier and colleagues, funded by the U.S. Department of Justice, revealed a troubling pattern: when fathers are accused of abuse and counter with alienation claims, courts often side with the father. In fact, in cases where a mother alleged child abuse and the father accused her of alienation, it doubled the likelihood that the mother would lose custody compared to abuse cases without an alienation counterclaim[14]. Many mothers in such scenarios saw the court transfer custody to the father (the alleged abuser) after the mother’s credibility was undermined by accusations of “alienating” behavior. The 2020 study found that courts rejected mothers’ abuse claims at alarmingly high rates, especially when alienation was raised - two-thirds of these mothers were portrayed as mentally unstable or malicious and lost custody as a result. In other words, the concept of parental alienation, when misused, has sometimes been a weapon to discredit abuse victims in court.

A high-profile illustration occurred in a 2023 case in Utah: despite previous findings by child protection authorities that a father had abused his kids, a court accepted the father’s claim that the mother was alienating the children, and ordered the children removed from the mother and placed with the father[14]. The judge’s order did not even mention the substantiated abuse history. The children (in this case, teenagers) were so distraught at being forced to live with the father they feared that they barricaded themselves and went public on social media, causing an outcry. This case and others highlight that courts can indeed make grave errors - either by overlooking a manipulative parent’s behavior until it’s too late, or by accepting false alienation claims and punishing a protective parent.

The error rate in alienation-related cases is difficult to quantify, but experts agree it’s significant enough to warrant concern. A 2019 analysis of hundreds of custody opinions found that when mothers alleged fathers had abused the child, courts ruled against the mother about 75% of the time if the father alleged alienation, versus around 55% of the time without alienation claims[14]. Thus, the introduction of “parental alienation” in an abuse context shifted outcomes strongly in favor of the accused (usually fathers in that dataset). From one perspective, this suggests courts are often failing to protect children from actual abusers by instead blaming the other parent for alienation. On the other hand, family court professionals also report cases where severe alienation by one parent is not remedied until the situation is dire, because judges are hesitant to remove a child from their preferred (but psychologically abusive) parent. Both types of errors stem from the difficulty of disentangling truth in “he-said, she-said” family conflicts and the controversial nature of the alienation concept.

Legal trends and reforms: In response to these challenges, there have been growing efforts to improve how courts handle parental alienation. Some notable trends and developments include:

-

Specialized training and guidelines: Recognizing the complexity, some jurisdictions have issued guidelines for judges and professionals. For example, the Family Justice Council in the UK released new guidance in Dec 2024 on handling cases of a child’s resistance/refusal of contact and allegations of alienating behavior[15]. This guidance compiles best practices to help courts distinguish alienation from justified estrangement and to keep the child’s welfare paramount. It was prompted by controversial cases and aims to ensure a more balanced approach (e.g., involving psychological experts carefully, considering both abuse and alienation possibilities, etc.).

-

Family court services programs: Agencies like CAFCASS (England/Wales) and some U.S. family courts have implemented programs such as “Separated Parent Information Programs” (SPIPs) and reunification therapy orders. SPIPs educate high-conflict parents on the harm to children from ongoing conflict and alienation[7]. However, their success is limited if an alienating parent is uncooperative (many alienators don’t see their behavior as wrong)[7]. Reunification therapy, sometimes in the form of intensive workshops or “family bridges” camps, is another tool courts order in severe cases - essentially therapy retreats aiming to repair the child’s relationship with the rejected parent. These have mixed reputations: some families report success, but others criticize them as coercive “reprogramming” camps. Nonetheless, the existence of such programs shows that courts are experimenting with remedies once alienation is identified.

-

Legal statutes: A few countries have enshrined parental alienation into law. Brazil pioneered this by passing Law 12.318 in 2010, explicitly defining “parental alienation” as harmful and giving courts power to sanction it. Brazilian courts can impose penalties ranging from fines and supervised visitation to transferring custody if a parent is found to be alienating. There have even been moves to criminalize severe parental alienation in Brazil, with proposals for prison terms for egregious cases. Mexico had laws in some states recognizing the concept (though one such law was later repealed amid controversy). In Italy, family courts have occasionally invoked parental alienation in decisions, and some other Latin countries have followed Brazil’s lead with similar statutes. In the United States, no federal law specifically addresses parental alienation, but many state laws do address interference with custody or visitation (sometimes called “custodial interference” or “visitation interference”). These laws, while not using the term parental alienation, make it a violation (even a misdemeanor or contempt of court) to wrongfully withhold a child from the other parent or undermine custody orders. For example, some states can modify custody if one parent consistently undermines the child’s relationship with the other parent (effectively a legal remedy for alienation). Advocates in the U.S. have periodically pushed for explicit recognition of parental alienation in statutes or the DSM, but those remain contentious. Notably, in 2020 the Colorado Supreme Court ruled in one case that severe parental alienation constituted child endangerment, providing a precedent to treat alienation as a form of harm justifying custody change[14]. This kind of ruling is now cited by lawyers in other states to argue that alienation equals abuse.

-

Professional skepticism and safeguards: On the other side, there’s been pushback to ensure courts do not misuse the alienation concept. The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) in the U.S. has cautioned judges about admitting “parental alienation” testimony, arguing it lacks a scientific basis and can obscure legitimate abuse[14]. In 2022-23, a UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women sounded an alarm about parental alienation in custody cases, calling it a “pseudo-concept” that is often used against mothers. The UN Human Rights Council report (2023) even recommended that courts ban the use of the term “parental alienation” because of its potential to undermine abuse claims. Some jurisdictions (like Spain in 2021) have indeed issued guidance to avoid the term in legal proceedings, focusing instead on specific behaviors. These developments reflect that while many see parental alienation as real, there is also an effort to ensure it’s not misapplied or accepted uncritically.

Overall, the legal system is in a delicate balancing act: how to protect children from an alienating parent’s emotional abuse, without inadvertently punishing a parent who may be protecting a child from genuine abuse. The trend in policy is toward better training - encouraging judges to consider both possibilities. We are also seeing more cases where courts do take decisive action in clear alienation scenarios (e.g., changing custody to the targeted parent, ordering therapy). Such interventions can be very effective if done early - many formerly alienated children have recovered relationships when courts enforced reunification and the alienator’s influence was checked. However, heavy-handed or misinformed interventions can cause harm too (e.g., removing a child from a primary caregiver wrongly). This underscores why data-driven, educated approaches are so crucial. The next section will look at the broader societal implications, but one key point here is: family courts are beginning to recognize parental alienation as a serious child welfare issue, yet the implementation is still evolving amid debate and the need for safeguards.

Navigation

| ← Part 3: Harms and Consequences | Part 5: Systemic and Societal Impact → |